In the early days of the pandemic, a group of graduate students with ties to Mexico came together in an effort to help people in that country understand its confusing COVID-19 detection program. What started as a one-article collaboration blossomed into Mexicans in Statistics and Health, an initiative committed to explaining complex scientific issues in everyday language.

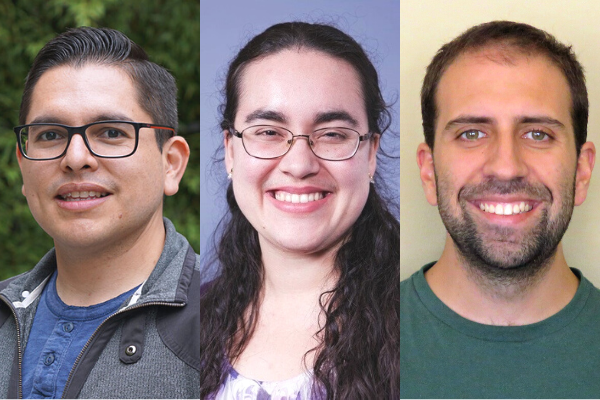

It started with Ernesto Ulloa, a biostatistics doctoral student at the University of Washington School of Public Health.

“There was a system that was being used to detect COVID-19 cases in Mexico and count them, and I was really curious to understand how it was working,” said Ulloa.

Ulloa recruited fellow biostatistics PhD students Natalie Gasca and Antonio Olivas-Martinez to help with the article, along with Susana Lozano Esparza, a PhD student in the SPH Department of Epidemiology. Pedro Orozco del Pino, a PhD student at the University of Michigan, and Jesús Daniel Arroyo Relión, a postdoc at the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University. Rounding out the group is Alfredo Garbundo Iñigo, a faculty member at Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology (ITAM) where Ulloa, Orozco del Pino, and Arroyo Relión received their undergraduate degrees.

“I felt that being part of the group was one very direct way that I could contribute and use my expertise to benefit the general public as well as family, friends, and extended relatives,” said Gasca. “And it is helpful for me, personally, to feel like I’m helping other people make decisions and understand a little bit better what’s going on in the world around us.”

Since that first article, the group has written two additional pieces: one about COVID-19 testing and another about vaccines. Their varied perspectives and experiences facilitated robust discussions that resulted in more comprehensive story content.

“I would think I knew something about a topic but would then listen to other members who had very good questions about ‘Why does this happen?’ and I would think ‘I was supposed to know that because I’m a medical doctor’ and then I would have to go do some research on it. Having everyone’s opinions while we were writing was very rewarding,” said Olivas-Martinez.

“All of our backgrounds and interests have come together nicely. Even if the expertise is not within our group, we know people who we can ask for other perspectives, which is super valuable,” said Gasca.

As initial work got underway, the group encountered a major challenge.

“I had never written anything for non-academics; only articles that were for a journal. Trying to translate all of my knowledge to people who may not have the same background as me has been an eye-opener. It’s harder than I thought it was going to be,” said Lozano Esparza.

“We learned a lot about how to write through trial and error with our friends and families. I remember we sent out the first article and got so many comments back that we basically had to redo it. I don’t think that happened nearly as much with the second and third articles,” said Orozco del Pino.

Gasca agrees, “The whole idea of science communication was something that I was interested in but hadn’t had any practical experience doing; actually sending something out into the world and saying ‘Here’s what I think about this topic’ and trying to do it in language, as well as imagery, that was understandable and accessible to a lot of people.”

So has the group’s work had any impact?

“A nice surprise for everyone was when we were cited for the first time,” said Lozano Esparza. “The University of California-San Francisco published a case report talking about Mexico and its handling of COVID cases, and they used our first article to help understand the system of counting cases of COVID. We were all very excited that we actually helped other researchers better understand Mexico’s case system.”

Gasca noted that after reading a draft of the group’s vaccine story, her dad used the information to spark discussions with coworkers.

“He would ask, ‘Hey, are you going to get your vaccine? What are you thinking about this? Do you want to trust somebody who’s just spouting rumors or somebody who has a bit more training in this topic?’ I think he’s had fun sharing with his coworkers, which is a really cool part of this that I didn’t realize. It’s not just people who click on a website who can share our information but people who have access via social media or other types of networks who can benefit and learn about these topics.”

“I have also noticed that people share the articles with family or friends,” said Arroyo Relión. “Sometimes they comment that they have learned new things. For example, with COVID-19 tests, people didn’t know that there are different tests. Having some reference that explains things carefully and comments about when to use one or the other was useful for people.”

All agreed that their experience with Mexicans in Statistics and Health, while a lot of work, has been gratifying, although the influence of their work came as a bit of a surprise.

“It’s been nice to know that, as a student, you can still have an impact in your country, even though you’re here in the States. I feel like I have made an impact, even if it’s small, to help people back there using the information I’ve learned here. A lot of my scholarships come from the Mexican government so it’s nice to kind of pay it forward,” said Lozano Esparza.

“It’s good to know that even though you’re a student, you know enough about things that you can actually help with science communication. Sometimes, as a student, you feel like you’re still learning, that you do not know anything yet and have to wait until a later stage of your career. But I think that’s not true and this has taught us, or at least me, that I have a lot to offer even as a student. And that’s very empowering,” said Orozco del Pino.

Looking ahead, Ulloa said “We want to keep working on topics related to statistics and health. Even though our effort was born out of COVID, we are eager to write about topics that are not necessarily pandemic related.”

— Deb Nelson, UW Biostatistics Communications